Theater

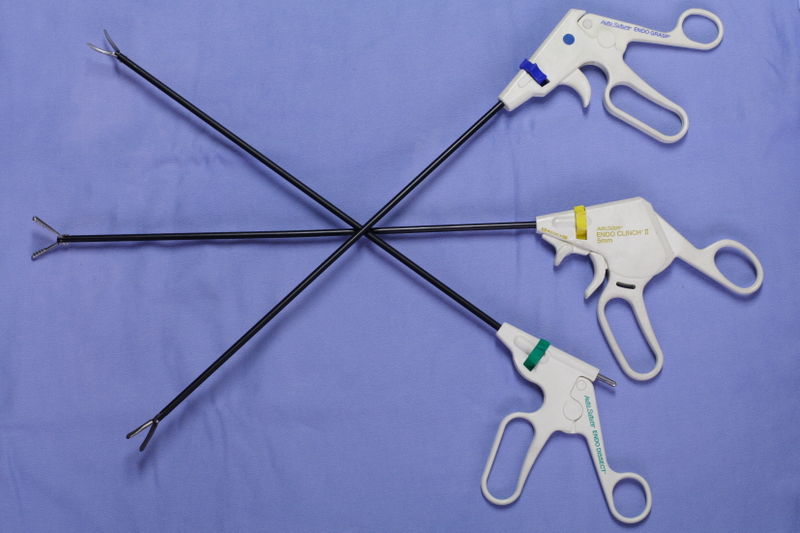

In the mornings when I arrive at the operation theaters, I see a list of different surgeries happening that day. There may be a cholecystectomy in one room, or a knee replacement surgery in another, a thyroidectomy happening now, or a brain biopsy scheduled in a few hours. If I hadn’t seen a particular surgery before, I can decide to scrub in and see it. Almost all the surgeons I have met in the operation theaters thus far have been very nice and welcoming in having a medical student walk in to see them work.

In my experience these past two months so far, the name “operation theater” lives up quite to its name. Going to the surgical theater is a lot like going to a movie theater and picking out which show to see. As I don’t watch a lot of movies nowadays, coming to the operation theater is my way of seeing something new and intriguing on my surgery rotation. Should I first see the long epic drama of the femoral-popliteal bypass graft or the short but graphic action blockbuster of the below knee amputation? Or perhaps I’m in the mood for a mystery flick: the exploratory laparotomy.

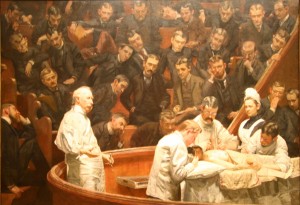

It’s no accident that in the UK, what we Americans call the “operation room” is what the British call the “operation theatre.” Historically in the 19th century, surgeries in England were performed on a stage surrounded by an audience of spectators who were curious to watch. This was before the development of modern sterilization techniques, anaesthesia, or even sterile surgical gloves, and the surgeons of the day would perform the procedures in their street clothes with just a white apron to shield them from blood stains. They would have to work quickly and swiftly to minimize the duration of pain on patients who are often fully awake. Although all of this dramatic showmanship and spectator seating have since been done away with with the development of modern standards of hygiene and privacy, the term “theater” still lingers today in the UK in reference to the “operation room.” Today, if you come to London for clinical rotations, you can still visit some of the world’s oldest surviving operation theaters, now converted into museums.

I’m grateful to be doing my surgery rotation in the UK, one of the historical centers of surgery. Several of the major players in the history of modern surgery were British, like Joseph Lister, who pioneered the use of antiseptics in surgery in the mid 1800s, or Lawson Tait, often considered the father of gynecological surgery. At Queen’s Hospital, the hours have been reasonable and curriculum very flexible, and most attendings like teaching students. You could easily walk into a surgical theater, ask if you could observe or follow the doctor, and most doctors would be more than happy to have you observe and participate. Because of this, I’ve seen quite a variety of surgeries in diverse specialties, such as ortho/trauma, gyne, ENT, GI, vascular, and neurosurgery. I’ve also spent time in anaesthesiology, seeing the “other side” of the patient during surgery, as well as a day in the endoscopy clinic because I hadn’t had the chance to see one before in my previous rotations. The educational opportunities abound here. Being a student here is like being handed a special ticket (which I have to say we do pay a lot for) for unlimited showings at a movie theater. It’s up to us as to how to make use of that ticket.

Operating theatre!!!

Hi Benji. I just got accepted to AUC and I am VERY EXCITED! After reading your blog, I feel like I have all the information I need. However, I was looking at your recommended blogs of other people, and I saw the blog about the guy who failed out of med school. This got me thinking. As excited as I am, I need to be realistic and see not to fall in the same path as students who tried so hard and could not make it for whatever reason. So all this to say: how did you keep your head above water, and strive in all your classes? Was it smarts? Study-habits? I know not one thing leads to success, but a combination so I would love to hear your input. Thank you! My excitement is slowly turning into nervousness!

Hi Nou,

It’s natural to be both excited and nervous for med school. Even now, I’m still both excited and nervous for what’s to come, like new rotations, step exams, and the match process. It’s definitely important to have a realistic view. Some people get accepted into medical school and think the hardest part is over and that the rest is smooth sailing, but it’s important to know that it’s just the beginning, and that learning medicine requires a lot of disciplined and dedicated work. Studying has to become a habit and hobby. Some people become too excited to be in a new atmosphere that they lose focus on what they came to the island to do (and paid a lot of tuition for). I’d say keep up with the material everyday, share your pains with your friends from class, and don’t be discouraged if you don’t do as well as you wanted. 🙂

Benji

Hi Benji! I was just wondering, when you did your rotations at these different places, did you have to pay different rents for each place you went to?

Hi Alfred,

Yes, we have to find our own accommodations and pay our own rents wherever we end up going for rotations. Some hospitals in England may provide on-hospital dormitory-style housing, but you’d still have to pay for it. It is not included in tuition. Best of luck.

Benji