Introduction to Clinical Medicine

Today in Introduction to Clinical Medicine (ICM), we had our physical examination “check-off” in which we were tested on performing all the physical examination skills we learned this semester in front of the professor. It went well, and I can now say that I am finished with ICM 3! Onward to ICM 4 next semester!

About ICM

Intro to Clinical Medicine (ICM) is a course we take for four semesters, starting with ICM 2 in second semester, ICM 3 in third semester, ICM 4 in fourth semester, and ICM 5 and 6 in fifth semester (**UPDATE** As of January 2014, first semester students also take ICM, but only once every 2 weeks). Each course is 4 weeks long (except ICM 5/6, which last an entire semester), two hours each, consisting of a combination of lectures and small-group “labs” in which we learn to interview patients and perform physical exams to prepare us for our clinical years. We also go to Harvey Lab where we learn how to identify abnormal heart sounds from a cardiac patient simulator (a “robot”). We have reading assignments from Bates’ Guide to Physical Examination and History Taking and take three graded quizzes over the reading.

For ICM 5 during fifth semester, we will discuss many clinical cases during small groups, learn to write write-ups and report our cases. We will also do male and female genital and breast exams on real people (who are paid to do this), as well as go to local hospitals and clinics in St. Maarten to do two different clinical rotations.

Interviewing Patients

Last semester in ICM 2, we learned how to introduce ourselves, pace an interview, and ask questions. We learned how to get a patient to open up to talk with us and feel that they are cared, and build rapport with patients. We learned why it is important to address more than just the patient’s problems, but also his or her emotions, relationship with others, daily lives, and understand his or her story as a whole person. This semester, we learned how to take a patient’s family history, social and personal history, and review of systems. We learned how to talk with older patients, and how to ask more personal questions such as a sexual history. We learned how to write case reports and problem lists.

In front of the class, all of us get the opportunity to practice interviewing with simulated patients (actors) who present a variety of clinical problems, social backgrounds, ages, and personalities. Interviewing as a doctor is more difficult than I thought, and is nothing like the interviewing I did as a pre-med student when I was volunteering at the clinic. I’m glad I have the chance to make the necessary fumbles now and learn from them so that I will be better prepared for my clinical rotations next year and beyond.

I really enjoyed interviewing, and watching my classmates interview. Every patient we interviewed is very different, presenting cases as simple as a nice, 65-year old lady with a urinary tract infection, to as challenging as a 22-year old patient with a uncooperative, violent attitude who has a history of drug use and risky behaviors, and showing signs of AIDS. How do we get a patient like this to reveal intimate details to complete strangers? It’s quite insightful to see how each of us handle the interviews, the different styles different students use, and the feedback we get from the actors on how they felt as a patient during the interview.

Each patient is also like a mystery novel revealing more and more of a complete story as the interview progresses. It’s fun to try to figure out their conditions.

Physical Examinations

Last semester we learned how to examine the eyes and ears with the ophthalmoscope, how to conduct hearing and vision tests, take blood pressure, check lymph nodes and more. We learned what to expect during our examinations when the patient has certain clinical problems. This semester, we learned how to examine the abdomen, such as percussing the body to find the liver and palpating it. We learned what to do for chest examinations, such as palpating for fremitus, auscultating for abnormal breathing sounds, and percussing to locate the diaphragm. We also learned how to do a physical examination on the heart, such as auscultation of the aortic, pulmonary, tricuspid, and mitral valves, and palpating for heaves and thrills.

Physical examination is not easy. It took me a long time just to hear the S2 split (which is when the second heart beat splits into two separate sounds when you breathe in). It was also a little tricky the first time I used an ophthalmoscope to inspect the fundus (back of the eye). As we practiced the physical examinations on each other in class this semester, it was difficult learning thrill (of a heart) would feel like, or what a gallop with murmurs would sound like on a real body (as opposed to the cardiac patient simulator in Harvey lab), as most of us are healthy. However, we won’t know what’s abnormal until we first learn to know what’s normal, and we have plenty of experiences in this now.

Some Tips for ICM:

- Do the readings in Smith, Bates, and Kochar! They have a lot of valuable information that you will use and encounter over and over in your future practice, especially as a primary care physician. Plus, it has the material you need for the three quizzes and final to pass the class.

- Don’t put off ICM! It may not require hours of rote memorization as Biochemistry or Med Micro, but it has its own challenges, and is one of the most relevant and practical classes you’ll take here during Basic Sciences. As there is a knowledge component to medicine, there is also a skill component as well. ICM gives you a framework to develop these skills.

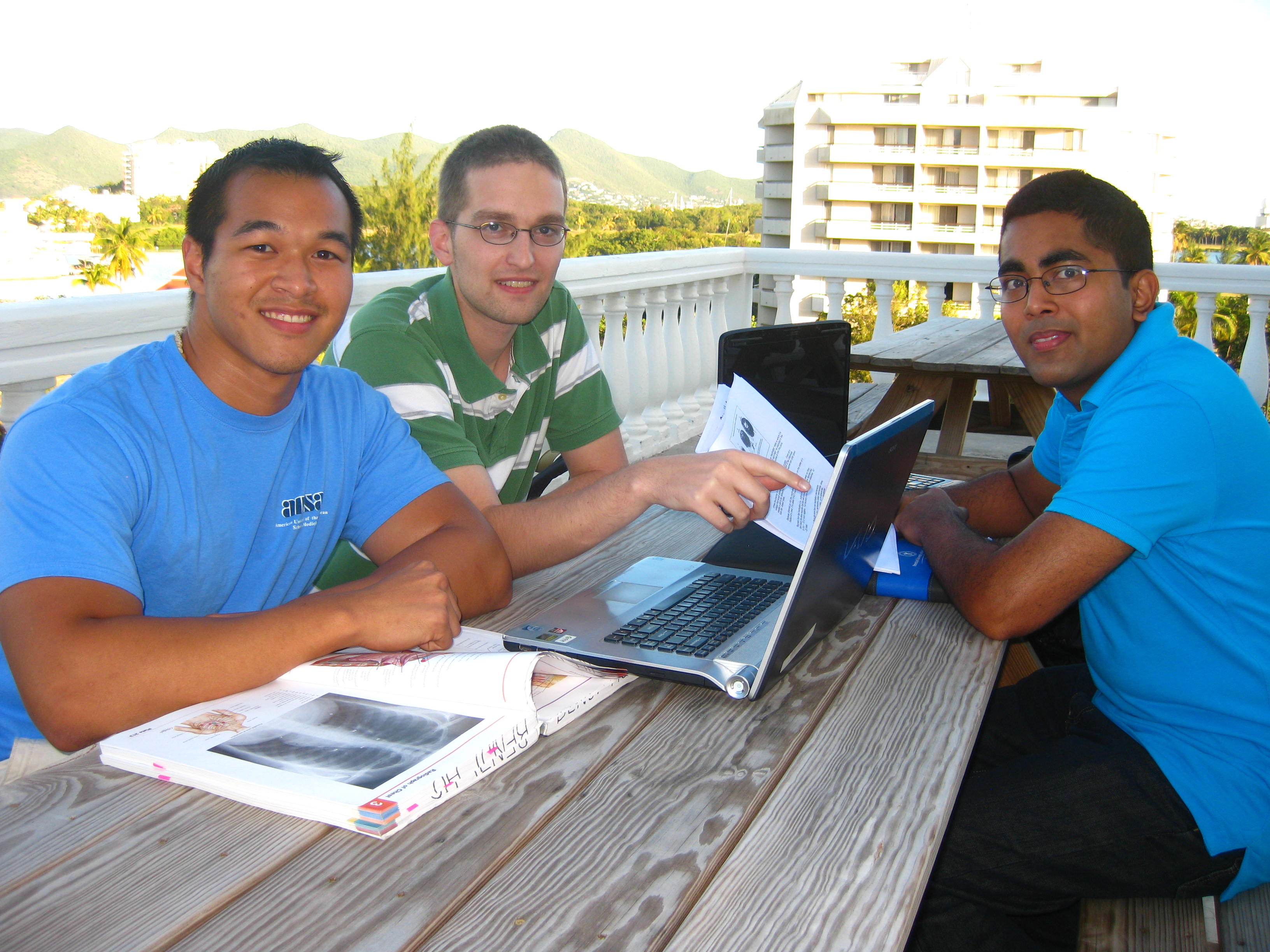

- Practice, practice, and practice! What we learn in ICM is only a framework of skills to build on, and like any other skill, mastery takes practice. I may not be able to detect an abnormal abdominal aorta when I palpate it now, but with the basic knowledge I take with me from ICM and enough extra practice on enough people I eventually will be able to do so. It’s amazing how an experienced doctors can understand what’s going on inside of the body simply by listening, feeling, and seeing what’s on the outside. Performing the physical examination is a skill and an art, and with enough practice and experience, we’ll develop the doctor’s “healing hands.” So meet with your friends outside of class and practice on each other, and practice enough so that you’ll know what to do without the cheat-sheet checklist (which you obviously can’t take with you into the office in your future practice, or to the Physical Exam Competency Test you take during fifth semester).

- Have fun! It’s one of the few classes we take with lots of interaction with our classmates. This is a class where we learn best through cooperation.